Instruments

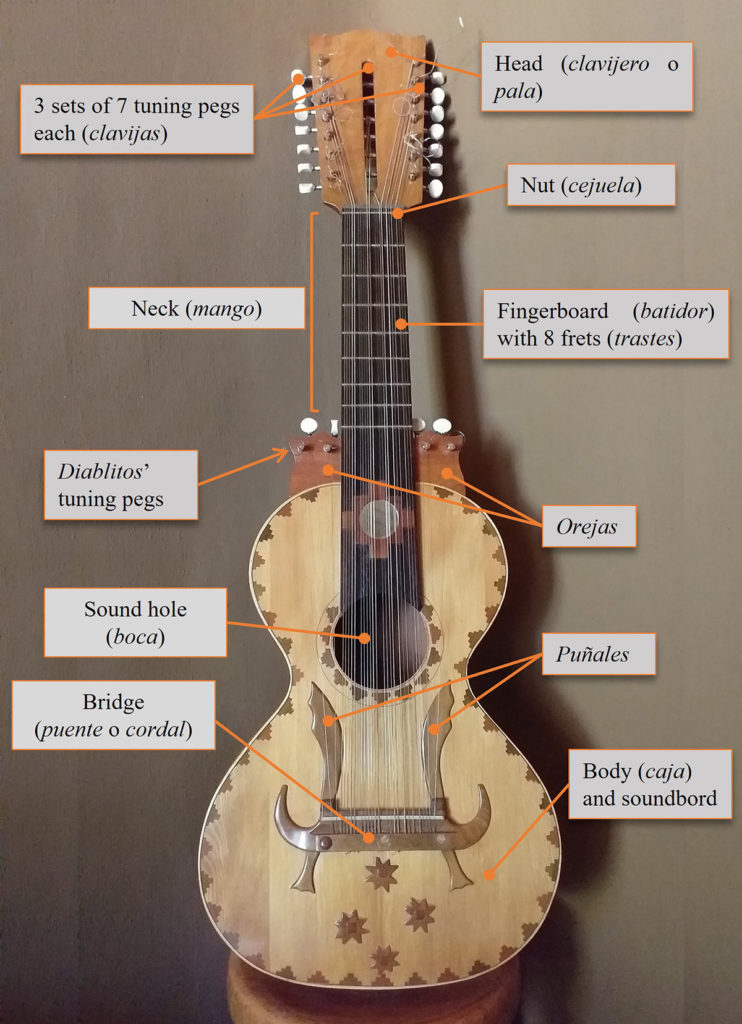

Fig. 1.1. The Chilean guitarrón and its parts. Instrument owned by Erick Gil Cornejo, made by Manuel Basoalto Maturana from Pirque (courtesy of Erick Gil Cornejo).

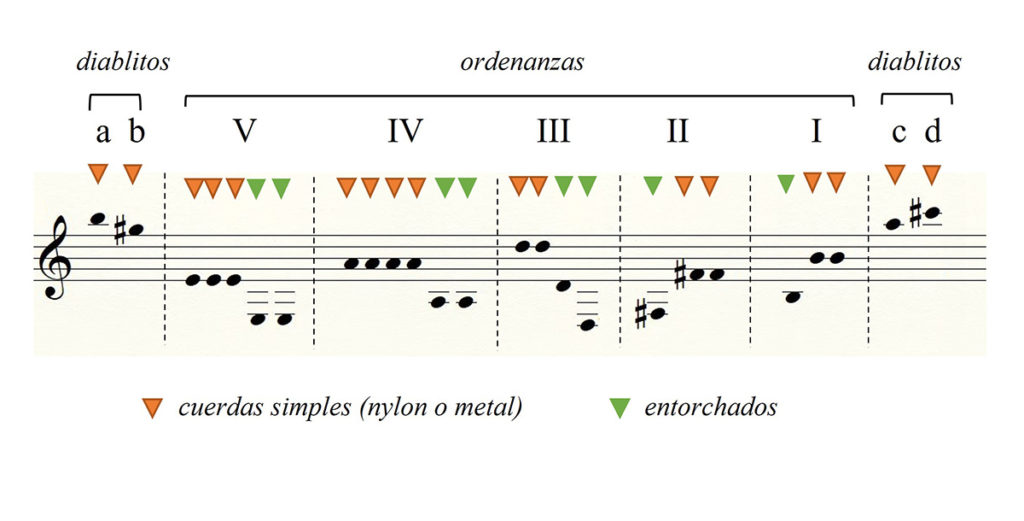

Fig. 1.2. The tuning of the guitarrón. The tuning may vary from one performer to another due to the type of strings and the distribution of octaves within the courses.

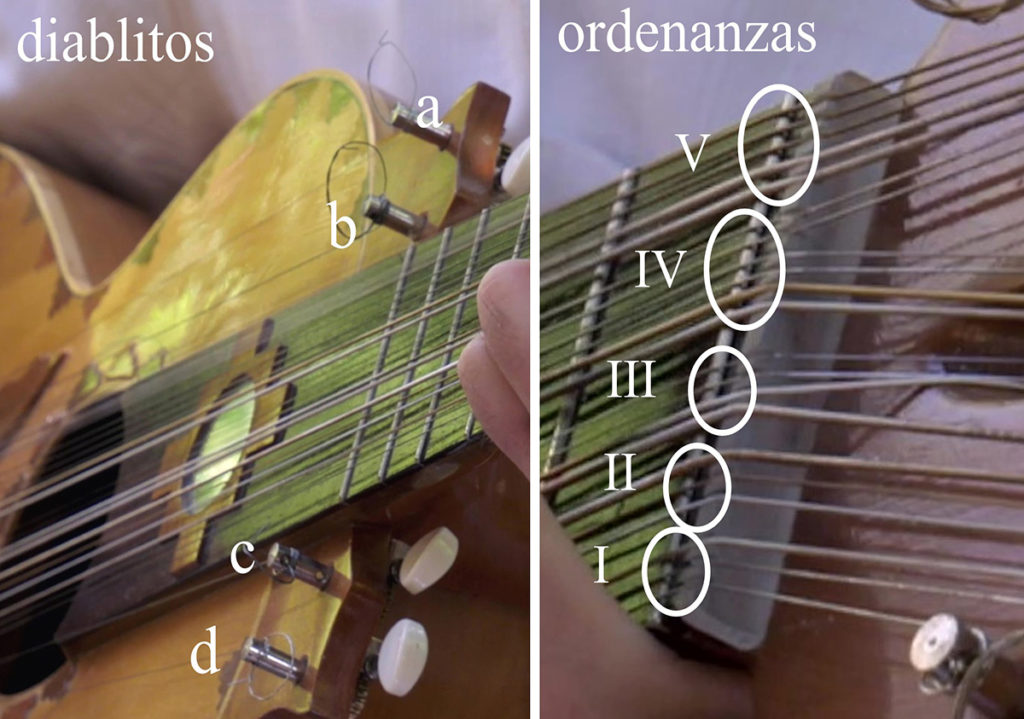

Fig. 1.3. The stringing of the guitarrón with the 5 principal courses (21 strings) and the 4 diablitos (side strings outside the fingerboard).

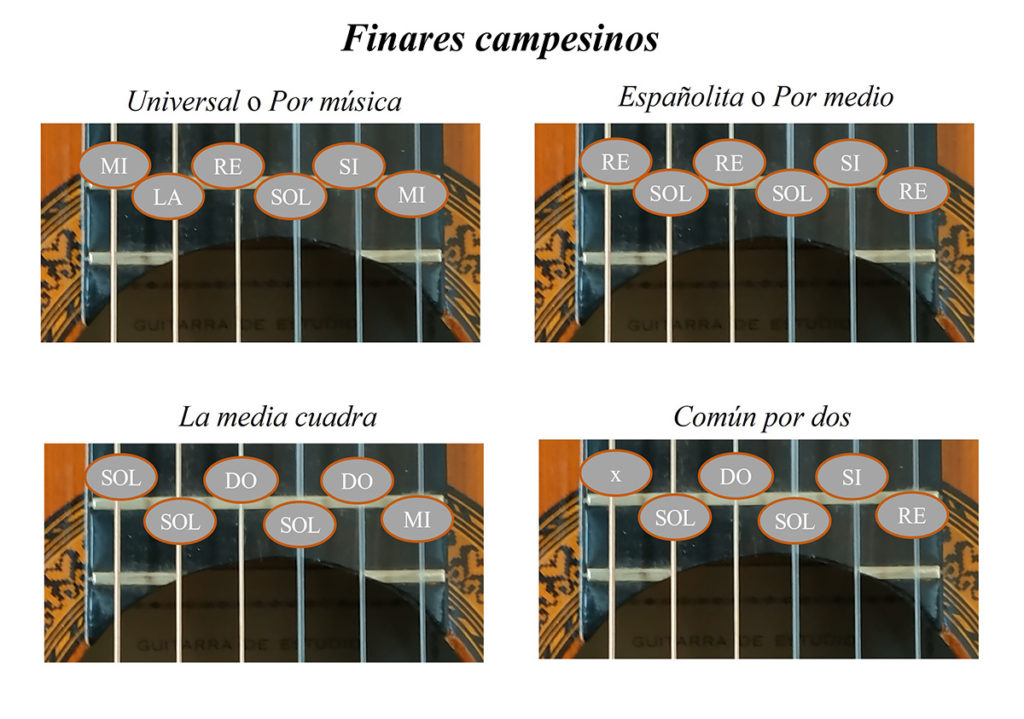

Fig. 1.4. Some examples of the tuning of the Chilean guitarra traspuesta. The second (españolita or por medio) is the tuning used by Roberto Carreño in the video on this page. The media cuadra has two strings in unison, whereas in the común por dos the tuning of the sixth string can be freely chosen.

The instruments: the guitarrón and the guitarra traspuesta

In canto a lo poeta, music and instrumental practice are placed at the service of the poem with its tempos, rhythms and metrical forms. At the same time, the instruments make a key contribution to creating special musical atmospheres and moods during the performance, both for the singers and the audience. Although canto a lo poeta has a collective dimension, as several performers intervene within the same performance, each singer is a soloist and is accompanied by only one instrument at a time. The instrumentation, as well as the performance styles and techniques, are the same for canto a lo divino and canto a lo humano.

In the video Canto a lo poeta. Guitarroneros and Poet-Singers from Central Chile, Roberto Carreño and Erick Gil play the guitarrón and the guitarra traspuesta.

The Chilean guitarrón. Cultural and aesthetic characteristics of the instrument

The Chilean guitarrón belongs to a large family of American chordophones clearly related to the guitar with four or five courses (cori or multiple string groups) that the Spanish introduced to the Americas. The American instruments are not rough copies of the 19th- and 20th-century guitar, but original local interpretations of older European models. At the same time, however, the Chilean guitarrón is unlike any other chordophone in Latin America in terms of the overall number of strings, as well as their atypical distribution in the courses, and the presence of diablitos (little devils), secondary strings outside the fingerboard. The Chilean guitarrón derives from the Spanish guitars of the colonial era, but the lack of documentation until the end of the 19th century, when the instrument had already assumed its current configuration, prevents us from reconstructing the intermediate steps of its development, for which there are various theories. According to some scholars, local makers and musicians may have multiplied unisons and octaves in the tuning to recreate on the European chordophone a sound with the dense timbre, rich in harmonics and percussive playing, that characterises the Amerindian aesthetics of the indigenous aerophone bands throughout the southern Andean area. But according to others, they were meant to reproduce the sounds of the organ and harpsichord on the guitar, since these instruments were not always readily available in the Chilean churches at the time. Throughout the 19th century, the guitarrón was also found in urban contexts but then gradually fell out of favour and barely survived in the surrounding countryside. Relegated to the outskirts of the city, the guitarrón was mostly used to accompany canto a lo poeta, and especially canto a lo divino, felt to be the quintessence of that rural world with its archaic traits. By the mid-20th century, very few guitarrones could still be found in the Pirque and Puente Alto area. Thanks to the efforts of local enthusiasts, such as the Santos brothers and Alfonso Rubio, and a few researchers, including the multifaceted musician Violeta Parra, the instrument gradually reacquired its popularity in Chile extending out from this circumscribed area. Today, the guitarrón is a resurgent, prestigious instrument, endowed with a strong identity and is now also used outside the traditional sphere in contexts and genres far removed from folk music.

Description of the instrument [fig. 1.1.]

Despite its name, the guitarrón or guitarra grande (literally large guitar) has slightly smaller overall dimensions than the modern guitar, except for the depth of the body, which tends to be greater. The guitarrón illustrated here has a figure of 8 shape and a flat bottom, reminiscent of the elongated forms of the early guitars but with more pronounced curves. The round sound hole on the soundboard is positioned at the end of the fingerboard. The bridge has two symmetrical side extensions (puñales – daggers) on the soundboard to make it more stable and able to withstand the considerable tension produced by the twenty-five strings. The neck is relatively short and the fingerboard has seven or more frets, originally movable and made from tied-on braided gut strings, now usually replaced by the same number of fixed metal bars. The characteristic large headstock houses twenty-one pegs or small keys, divided into three parallel series of seven each. Again, metal tuning pegs have now replaced the wooden pegs, which are more laborious to use and hold the tuning for less time. Another recent innovation is the use of imported wood to replace wood from no longer available indigenous trees. The instruments often feature ornamental elements (mother-of-pearl decorations, mirrors inserted in the fingerboard and wood inlays), with symbolic motifs, such as crosses, stars, doves, hearts and church naves. The two puñales also often have decorative elements. The stringing is the most original aspect of the instrument [Fig. 1.2 and 1.3]. Unlike the guitarra traspuesta, the guitarrón has a well-established fixed tuning. This means that each performer can only make a few subtle individual variations, mainly in the choice of string materials and gauges, or in the absolute tuning, which can generally vary by two semitones (with the fourth course, considered the tonal centre of gravity of the instrument, tuned to G, G# or A). In recent years, instruments have been tuned in higher keys to suit the vocal register of female performers.

The twenty-one main strings are distributed in five groups or courses (órdenes or ordenanzas), tuned in intervals of fourths, except for the interval of a major third between the second and third course. Each course has from three to six strings, tuned in unison, octaves or double octaves. The lowest note and some of the highest pitches are in the middle, in the third course, thus giving rise to a form of non-progressive tuning (i.e. the string sequence is not ordered from the lowest to highest).

Four shorter single strings called diablitos (little devils) or tiples (trebles or “little singers”) are in the high register. They are positioned on the same horizontal plane as the other strings, but outside the fingerboard, two on each side, and are tightened by pegs attached to two extensions (orejas – “ears”) of the soundboard near the neck joint. The diablitos are struck as open strings and are used to complete the harmony, emphasising certain cadences with their clear high ringing sound, depending on the style of the performer.

At the end of the 19th century, there were three types of strings: braided silk (entorchados), gut (cuerdas) and steel (alambres). Today, various gauges of standard guitar strings are used, either metal or nylon, or in mixed combinations. The diversity of materials and the uneven distribution of unisons and octaves in the five courses, together with the associated micro-variations in intonation, mean that the guitarrón has an extraordinary variety of timbre, producing the effect of an “ensemble” of several instruments playing simultaneously. Together with the wide tessitura (range) but with a predominance of the middle register, this makes the instrument particularly suitable for its main function of accompanying singing.

The guitarra traspuesta

The guitars used in Chilean rural folk music do not have any major morphological differences from the modern six-string model, except for the various tunings, which are unlike the standard tuning, here called por música or universal. The different tunings are called finares or afinares (from the verb afinar, to tune), and the guitar tuned in this way is called the guitarra traspuesta. More than fifty different tunings used by Chilean guitarra campesina enthusiasts have been recorded, some closely associated with the canto a lo poeta. The tunings vary according to geographical area and each cantor only masters a few of them. Such transposed tunings often transfer the four- or five-string pattern of early guitars to the six strings of the modern instrument, simply by doubling one or more notes [Fig. 1.4.] In general, the tunings obtained in this way are aimed at simplifying the positions of the left hand, so as to obtain chords with the maximum number of open strings, which are both very resonant and easy to play. The simplicity in the use of the left hand that this solution offers, however, entails the need to change tuning according to the different keys and entonaciones (melodies) by modifying the intervals between the strings as required. Consequently, the cantor will have to learn and memorise a large number of positions, since the same chord requires different fingering depending on the tuning adopted each time. This means that performing canto a lo poeta requires having a good memory not only for the texts but also for these technical musical aspects.

In the video on guitarra traspuesta, Roberto Carreño describes how the features of the instrument can make playing less arduous for the performers, who in the past were often called upon to accompany dozens of poets and cantores for hours on end.