Canto a lo Poeta. Guitarroneros and Poet-Singers of Central Chile

Fig. 0.1 Source: Archivio de Literatura oral y Traditiones Populares. Biblioteca Nacional Digital de Chile

Fig. 0.2. Pedro Tapia and Ana Monardes, cantores a lo divino, during the vigil for the feast of the Virgen del Carmen at El Tebal (Valparaíso). Source: Manuel Morales, Daniel González, Danilo Petrovich Mundana, Alta esfera, Ediciones MUCAM.

Fig. 0.4. Erick Gil and Roberto Carreño are both poets and guitarroneros.

The listening guide presented here was realized with materials collected during the recording of the edition of Zoom in on masters dedicated to the guitarroneros and poet-singers of Central Chile. We would like to thank the singers Erick Gil and Roberto Carreño, and the ethnomusicologist Claudio Mercado, of the Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, for their generous collaboration in the production of both multimedia publications edited by the Intercultural Institute of Comparative Music Studies.

Canto a lo poeta: origins and diffusion

Canto a lo poeta (singing in the manner of the poet) is an oral and sung poetry practice, accompanied by stringed instruments, performed by folk poets and singers in the rural areas of central Chile. From a historical point of view, this tradition is the result of the cultural syncretism that followed the conquest and colonisation of the Americas by the Spanish between the 16th and 18th centuries and, as such, it has remarkable similarities with other popular sung poetry widespread in Spanish-speaking America, from Mexico to Argentina. Several regional poetic traditions of this vast area are in fact characterised by the use of the same metrical forms common to the Iberian literary tradition. An obvious example is the décima espinela (see Formal analysis: metrical and musical structure). At the same time, however, they can be distinguished from each other by various local specificities, the result of independent developments that include the cultural contributions of the indigenous and mestizo populations, made in several ways: the construction of the poetic repertoire, the aesthetics of the musical components, and the modes and contexts of performances.

The Chilean canto a lo poeta has been documented in forms similar to the present form since the 19th century. Its gestation, however, is thought to have lasted over the previous three centuries, during the long, conflictual process of the colonisation of the southern regions of the Spanish-ruled Viceroyalty of Peru, to which the territory of present-day Chile belonged. The characteristically religious canto a lo divino is believed to have been the earliest form: the clergy (particularly the Jesuits) used to adapt religious texts to profane music, already spread by Spanish soldiers and colonists, in order to inculcate Catholic doctrine and knowledge of the Bible in the indigenous and mestizo populations. According to another theory, canto a lo poeta was said to have derived from a repertoire of liturgical psalmodic singing, gradually converted to private use. Canto a lo divino then gave rise to canto a lo humano, when folk cantores began to use the same poetic forms and melodies for secular and profane themes.

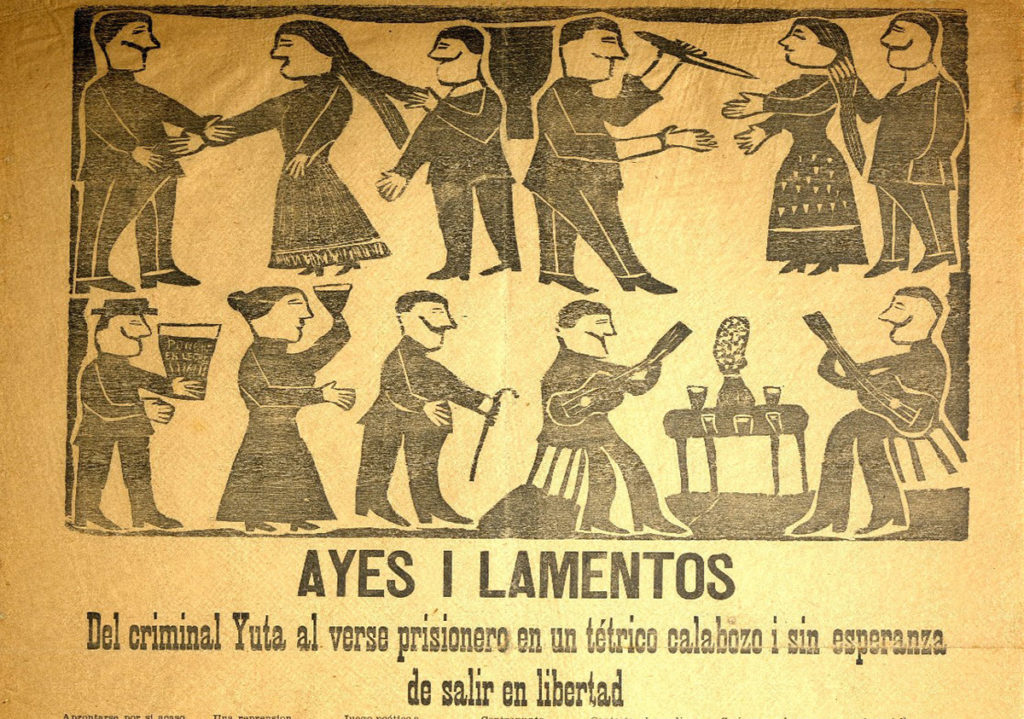

Between the late 19th and early 20th century, canto a lo poeta flourished and circulated widely within a broader popular literary system, also in written form, as witnessed by the lively production of the broadsheets of the Lira popular [Fig. 0.1.]. During the first half of the 20th century, however, following the urban and industrial growth of the country, the genre was gradually confined to the countryside and barely survived. Today, thanks to the efforts of pioneering researchers and a generation of local enthusiasts, canto a lo poeta and the guitarrón are enjoying a new lease of life, both in the preservation and transmission of traditional practices and in the creation of new forms, or in crossovers with other genres. A national survey recorded several thousand active cantores and payadores (poet-singers who take part in poetic improvisation contests), often in groups and associations. The area of diffusion of traditional forms of canto a lo poeta is now rural central Chile, the regions of Coquimbo in the north and Bio Bio (Concepción), almost 1,000 kilometres further south. Within the area of diffusion, several zones can be distinguished in terms of differences in musical styles and performing technique [Fig. 0.3.] For a detailed map of the presence of individual cantores and associations of canto a lo poeta, go to: http://www.sigpa.cl/ficha-elemento/canto-a-lo-poeta.

The poet-singers

The performer is primarily a singer. In some cases, he is also the author of the texts (and thus a poet), while at times he may simply set to music other poets’ poems, which, at least in the past, had been transmitted orally. Today, the singer is almost always also an instrumentalist, capable of accompanying his own singing or that of other singers and poets during collective performances, called ruedas. The instruments commonly used are the Chilean guitarrón and the guitarra traspuesta and, more rarely, the rabel, a threestringed instrument in the family of Mediaeval rebecs. Despite a few documented exceptions, in the past the cantor and the guitarrón player were only men: women performed other repertoires of dances and songs, which they accompanied on guitar or harp. Today, this division is no longer a hard and fast rule, and cantoras a lo poeta and guitarroneras (female poet-singers and guitarrón players) are now commonly found. The cantor is not a paid professional but enjoys the recognition and respect of the community for his or her gifts, skills and role as a living memory of events, forms of knowledge and shared values. Belonging to a largely oral-based culture, until a few years ago, the oldest singers were almost always illiterate peasants or animal rearers, yet capable not only of memorising many thousands of lines of verse concerning biblical stories and the most diverse topics, but also of creating their own versified narratives or philosophical reflections on the same topics, or improvising for hours during contests with other poets. Official culture has long had an ambiguous attitude towards these art forms. For example, canto a lo divino has only recently been accepted into the liturgical world of the Catholic Church, having previously been viewed with suspicion as an expression of a non sanctioned popular religiosity. In turn, the official secular (Eurocentric) culture has extolled the canto a lo poeta for its deep Hispanic roots while overlooking its non-European characteristics. More recent studies, however, have highlighted the importance of Amerindian and mestizo components, such as the musical aesthetics.

Repertoire and contexts

The repertoire of canto a lo poeta comprises canto a lo divino and canto a lo humano. Both use the same poetic structures (versos) and musical structures (entonaciones), while they differ significantly in the topics covered (fundados or fundamentos) and in the contexts and occasions when they are performed. The canto a lo divino is performed on religious holidays, during novenas in honour of the Virgin and the saints, or at funeral wakes and vigils [Fig. 0.2]. The velorio del angelito, i.e. a wake for a dead child is one of the most important and intense duties for a cantor a lo divino. The canto a lo divino draws its fundados from episodes in the Old and New Testaments (the Creation, Cain and Abel, the Birth of Christ, the Apocalypse, etc.) or from paraliturgical themes (the lives of the saints, the story of the wandering Jew, etc.). The canto lo humano, on the other hand, was originally associated with everyday rural life, in particular resting and recreation during community work, such as harvesting or threshing. The songs have various themes, ranging from events in ancient history to local stories and social and political current affairs; from knowledge of past centuries (such as astronomy, geography or arithmetic) to everyday sentimental and social life: love songs, serenades (esquinazos) and good wishes to newlyweds (parabienes). Another part of canto a lo humano is the paya, i.e. contests of poetic improvisation between singers (payadores), according to highly codified, complex schemes, in which the poets demonstrate their compositional virtuosity. In both cases, a lo humano and a lo divino, the original usual setting was the private, extended family world, with the participation of a small local community. In recent times, however, canto a lo poeta has also entered public settings, such as those of religious liturgy, in the case of canto a lo divino, or the stage, in the case of canto a lo humano and especially of paya, with numerous festivals and meetings of payadores (see Contexts and performances).

The video

The video shows excerpts from the performances of two singers: Roberto Carreño, originally from Placilla (Colchagua Province, about 150 km south of the capital, Santiago), and Erick Gil, originally from Pirque (in the metropolitan area of Santiago) [Fig. 0.4]. The recording was made in October 2020 at the home of ethnomusicologist Claudio Mercado in Pirque. The video is not of a complete performance, but only a few stanzas quoted from their respective compositions. In the first fragment, Roberto Carreño sings a décima (tenline stanza) a lo divino, on the theme of the story of Adam and Eve:

In the garden of earthly paradise / God placed Adam and Eve to test them, / to see if they were naturally good. / He said to them: “You shall not eat / from the tree of good and evil.” / But the woman, tempted / by a cunning snake, / picked the first fruit / out of sheer

curiosity.

In the second fragment, sung by Erick Gil, the subject is Por el agua (About water) and belongs to the a lo humano category:

On the puna [high plateau] the sun breaks through / bringing its warmth / steam rises from ice / and upwards gathers towards the sky. / One by one drops of rain / fall on the steep

rocks / and run clean down the crags on natural paths / forming rivers and streams / from

snowy peaks.

In the first two sequences, the singers accompanied themselves on the guitarrón. In the third, however, Roberto Carreño employs the guitarra traspuesta, that is, with a different tuning from the standard version (see Instruments). The subject of the text is the cantor a lo divino, his ethics and the responsibility that comes with possessing an artistic gift:

The cantor a lo divino / has a noble mission: / to sing from the heart / to each of his fellow humans. / He can’t be mean / with the gift that God has given him / he can’t be insincere / with his fellow cantores or expect flowers / if he doesn’t deserve them.

The original Spanish text of the stanzas are included in the subtitles of the video. The full text of the composition Por el agua is quoted in Formal analysis: metrical and musical structure.